Internet meme

| Internet |

|---|

|

|

|

An Internet meme, or meme (/miːm/, MEEM), is a cultural item (such as an idea, behavior, or style) that spreads across the Internet, primarily through social media platforms. Internet memes manifest in a variety of formats, including images, videos, GIFs, and other viral content. Key characteristics of memes include their tendency to be parodied, their use of intertextuality, their viral dissemination, and their continual evolution. The term "meme" was originally introduced by Richard Dawkins in 1972 to describe the concept of cultural transmission.

The term "Internet meme" was coined by Mike Godwin in 1993 in reference to the way memes proliferated through early online communities, including message boards, Usenet groups, and email. The emergence of social media platforms such as YouTube, Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram further diversified memes and accelerated their spread. Newer meme genres include "dank" and surrealist memes, as well as short-form videos popularized by platforms like Vine and TikTok.

Memes are now recognized as a significant aspect of Internet culture and are the subject of academic research. They appear across a broad spectrum of contexts, including marketing, economics, finance, politics, social movements, religion, and healthcare. While memes are often viewed as falling under fair use protection, their incorporation of material from pre-existing works can sometimes result in copyright disputes.

Characteristics

Internet memes derive from the original concept of "memes" as units of cultural transmission, passed from person to person. In the digital realm, this transmission occurs primarily through online platforms, such as social media.[1] Although related, internet memes differ from traditional memes in that they often represent fleeting trends, whereas the success of traditional memes is measured by their endurance over time. Additionally, internet memes tend to be less abstract in nature compared to their traditional counterparts.[2] They are highly versatile in form and purpose, serving as tools for light entertainment, self-expression, social commentary, and even political discourse.[3]

Two fundamental characteristics of internet memes are creative reproduction and intertextuality.[4] Creative reproduction refers to the adaptation and transformation of a meme through imitation or parody, either by reproducing the meme in a new context ("mimicry") or by remixing the original material ("remix"). In mimicry, the meme is recreated in a different setting, as seen when different individuals replicate the viral video "Charlie Bit My Finger." Remix, on the other hand, involves technological manipulation, such as altering an image with Photoshop, while retaining elements of the original meme.[4]

Intertextuality in memes involves the blending of different cultural references or contexts. An example of this is the combination of U.S. politician Mitt Romney’s phrase “binders full of women” from the 2012 U.S. presidential debate with a scene from the Korean pop song “Gangnam Style.” In this case, the phrase "my binders full of women exploded" is superimposed on a frame from Psy’s music video, creating a new meaning by merging political and cultural references from distinct contexts.[4]

Internet memes can also function as in-jokes within specific online communities, where they convey insider knowledge that may be incomprehensible to outsiders. This fosters a sense of collective identity within the group.[5] Conversely, some memes achieve widespread cultural relevance, being understood and appreciated by broader audiences outside of the originating subculture.[3]

A study by Michele Knobel and Colin Lankshear examined how Richard Dawkins' three characteristics of successful traditional memes—fidelity, fecundity, and longevity—apply to internet memes. It was found that fidelity in the context of internet memes is better described as replicability, as memes are frequently modified through remixing while still maintaining their core message. Fecundity, or the ability of a meme to spread, is promoted by factors such as humor (such as the comically translated video game line "All your base are belong to us"), intertextuality (as in the various pop culture-referencing renditions of the "Star Wars Kid" viral video), and juxtaposition of seemingly incongruous elements (exemplified in the Bert is Evil meme). Finally, longevity is essential for a meme’s continued circulation and evolution over time.[6]

Evolution and propagation

Internet memes can either remain consistent or evolve over time. This evolution may involve changes in meaning while retaining the meme’s structure, or vice versa, with such transformations occurring either by chance or through deliberate efforts like parody.[7] A study by Miltner examined the lolcats meme, tracing its development from an in-joke within computer and gaming communities on the website 4chan to a broader source of humor and emotional support. As the meme entered mainstream culture, it lost favor with its original creators. Miltner explained that as content moves through different communities, it is reinterpreted to suit the specific needs and desires of those communities, often diverging from the creator’s original intent.[5] Modifications to memes can lead them to transcend social and cultural boundaries.[8]

Memes spread virally, in a manner similar to the SIR (Susceptible-Infectious-Recovered) model used to describe the transmission of diseases.[9] Once a meme has reached a critical number of individuals, its continued spread becomes inevitable.[10] Research by Coscia examined the factors contributing to a meme’s propagation and longevity, concluding that while memes compete for attention—often resulting in shorter lifespans—they can also collaborate, enhancing their chances of survival. A meme that experiences an exceptionally high peak in popularity is unlikely to endure unless it is uniquely distinct. Conversely, a meme without such a peak, but that coexists with others, tends to have greater longevity.[11] In 2013, Dominic Basulto, writing for The Washington Post, argued that the widespread use of memes, particularly by the marketing and advertising industries, has led to a decline in their original cultural value. Once considered valuable cultural artifacts meant to endure, memes now often convey trivial rather than meaningful ideas.[12]

History

Origins and early memes

The word meme was coined by Richard Dawkins in his 1976 book The Selfish Gene as an attempt to explain how aspects of culture replicate, mutate, and evolve (memetics).[13] Emoticons are among the earliest examples of internet memes, specifically the smiley emoticon ":-)", introduced by Scott Fahlman in 1982.[14] The concept of memes in an online context was formally proposed by Mike Godwin in the June 1993 issue of Wired.[15] In 2013, Dawkins characterized an Internet meme as being a meme deliberately altered by human creativity—distinguished from biological genes and his own pre-Internet concept of a meme, which involved mutation by random change and spreading through accurate replication as in Darwinian selection. Dawkins explained that Internet memes are thus a "hijacking of the original idea", evolving the very concept of a meme in this new direction.[16] Nevertheless, by 2013, Limor Shifman solidified the relationship of memes to internet culture and reworked Dawkins' concept for online contexts.[17] Such an association has been shown to be empirically valuable as internet memes carry an additional property that Dawkins' "memes" do not: internet memes leave a footprint in the media through which they propagate (for example, social networks) that renders them traceable and analyzable.[11]

However, before internet memes were considered truly academic, they were initially a colloquial reference to humorous visual communication online in the mid-late 1990s among internet denizens; examples of these early internet memes include the Dancing Baby and Hampster Dance.[18] Memes of this time were primarily spread via messageboards, Usenet groups, and email, and generally lasted for a longer time than modern memes.[19]

As the Internet protocols evolved, so did memes. Lolcats originated from imageboard website 4chan, becoming the prototype of the "image macro" format (an image overlaid by large text).[19] Other early forms of image-based memes included demotivators (parodized motivational posters), photoshopped images, comics (such as rage comics),[21][22] and anime fan art,[23] sometimes made by doujin circles in various countries. After the release of YouTube in 2005, video-based memes such as Rickrolling and viral videos such as "Gangnam Style" and the Harlem shake emerged.[19][24] The appearance of social media websites such as Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram provided additional mediums for the spread of memes,[25] and the creation of meme-generating websites made their production more accessible.[19]

Modern memes

"Dank memes" are a more recent phenomenon, the phrase reaching mainstream prominence around 2014 and referring to deliberately zany or odd memes with features such as oversaturated colours, compression artifacts, crude humour, and overly loud sounds (termed "ear rape").[26][27] The term "dank", which refers to cold, damp places, has been adapted as a way to describe memes as "new" or "cool".[26][28] The term may also be used to describe memes that have become overused and stale to the point of paradoxically becoming humorous again.[29] The phenomenon of dank memes sprouted a subculture called the "meme market", satirising Wall Street and applying the associated jargon (such as "stocks") to internet memes. Originally started on Reddit as /r/MemeEconomy, users jokingly "buy" or "sell" shares in a meme reflecting opinion on its potential popularity.[30]

"Deep-fried" memes refer to those that have been distorted and run through several filters and/or layers of lossy compression.[31][32] An example of these is the "E" meme, a picture of YouTuber Markiplier photoshopped onto Lord Farquaad from the film Shrek, in turn photoshopped into a scene from businessman Mark Zuckerberg's hearing in Congress and captioned with a lone 'E'.[33] Elizabeth Bruenig of the Washington Post described this as a "digital update to the surreal and absurd genres of art and literature that characterized the tumultuous early 20th century".[34]

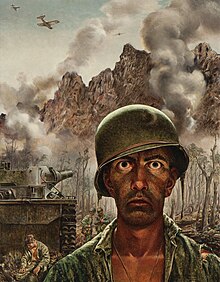

Many modern memes make use of humorously absurd and even surrealist themes. Examples of the former include "they did surgery on a grape", a video depicting a Da Vinci Surgical System performing test surgery on a grape,[36] and the "moth meme", a close-up picture of a moth with captions humorously conveying the insect's love of lamps.[37] Surreal memes incorporate layers of irony to make them unique and nonsensical, often as a means of escapism from mainstream meme culture.[38]

After the success of the application Vine, a format of memes emerged in the form of short videos and scripted sketches. An example is the "What's Nine Plus Ten?" meme, a Vine video depicting a child humorously providing an incorrect answer to a math problem.[39] After the shutdown of Vine in 2017, the de facto replacement became Chinese social network TikTok, which similarly utilises the short video format.[40] The platform has become immensely popular, and is the source of memes such as the "Renegade" dance.[41][42]

In 2022, the term brain rot became used to reflect a shift in how memes, particularly TikTok videos, were being interacted with. The term describes content lacking in quality and meaning, often associated with slang and trends popular among Generation Alpha, such as "skibidi", "rizz", "gyatt", and "fanum tax".[43] The name comes from the perceived negative psychological and cognitive effects caused by exposure to such content.[44]

By context

Marketing

The practice of using memes to market products or services has been termed "memetic marketing".[45] Internet memes allow brands to circumvent the conception of advertisements as irksome, making them less overt and more tailored to the likes of their target audience. Marketing personnel may choose to utilise an existing meme, or create a new meme from scratch. Fashion house Gucci employed the former strategy, launching a series of Instagram ads that reimagined popular memes featuring its watch collection. The image macro "The Most Interesting Man in the World" is an example of the latter, a meme generated from an advertising campaign for the Dos Equis beer brand.[46] Products may also gain popularity through internet memes without intention by the producer themselves; for instance, the film Snakes on a Plane became a cult classic after creation of the website SnakesOnABlog.com by law student Brian Finkelstein.[47]

Use of memes by brands, while often advantageous, has been subject to criticism for seemingly forced, unoriginal, or unfunny usage of memes, which can negatively impact a brand's image.[48] For example, the fast food company Wendy's began a social media-based approach to marketing that was initially met with success (resulting in an almost 50% profit growth that year), but received criticism after sharing a controversial Pepe meme that was negatively perceived by consumers.[49]

Economics & finance

Meme stocks are a phenomenon where stock values for a company rise significantly in a short period due to a surge in interest online and subsequent buying by investors. Video game retailer GameStop is recognised as the first meme stock.[50] r/WallStreetBets, a subreddit where participants discuss stock trading, and Robinhood Markets, a financial services company, became notable in 2021 for their involvement in the popularisation of meme stocks.[51][52] "YOLO investors" are a phenomenon that emerged during the COVID-19 pandemic, who are less risk averse in their investments compared to their traditional counterparts.[53]

Additionally, memes have developed an association with cryptocurrency with the development of meme currencies such as Dogecoin, Shiba Inu Coin, and Pepe Coin. Meme cryptocurrencies have suggested comparisons between meme value and monetary markets.[54][55]

Politics

Internet memes are a medium for fast communication to large online audiences, which has led to their use by those seeking to express a political opinion or actively campaign for (or against) a political entity.[14][56] In some ways, they can be seen as a modern form of the political cartoon, offering a way to democratize political commentary.[57]

Among the earliest political memes were those arising from the viral Dean scream, an excerpt from a speech delivered by Vermont governor Howard Dean.[58] Over time, Internet memes have become an increasingly important element in political campaigns, as online communities contribute to broader discourse through the use of memes.[59] For example, Ted Cruz's 2016 Republican presidential bid was damaged by Internet memes that jokingly speculated he was the Zodiac Killer.[60]

Research has shown the use of memes during elections has a role to play in informing the public on political themes. A study explored this in relation to the 2017 UK general election, and concluded that memes acted as a widely shared conduit for basic political information to audiences who would usually not seek it out.[61] They also found that memes may play some role in increasing voter turnout.[61]

Some political campaigns have begun to explicitly taken advantage of the increasing influence of memes; as part of the 2020 US presidential campaign, Michael Bloomberg sponsored a number of Instagram accounts (with over 60 million followers collectively) to post memes related to the Bloomberg campaign.[62] The campaign was faulted for treating memes as a commodity that can be bought.[63]

Beyond their use in elections, Internet memes can become symbols for various political ideologies. A salient example is Pepe the Frog, which has been used as a symbol for the alt-right political movement, as well as for pro-democracy ideologies in the 2019–2020 Hong Kong protests.[64][65]

Social movements

Internet memes can be powerful tools in social movements, constructing collective identity and providing platform for discourse.[3][66] During the 2010 It Gets Better Project for LGBTQ+ empowerment, memes were used to uplift LGBTQ+ youth while negotiating the community's collective identity.[67] In 2014, the viral Ice Bucket Challenge raised money and awareness for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis/Motor Neurone Disease (ALS/MND).[68] Furthermore, internet memes proved an important medium in the discourse surrounding the Occupy Wall Street (OWS) movement.[69]

Religion

Internet memes have also been used in the context of religion.[70] They create a participatory culture that enable individuals to collectively make meaning of religious beliefs, reflecting a form of lived religion.[71] Aguilar et al. of Texas A&M University identified six common genres of religious memes: non-religious image macros with religious themes, image macros featuring religious figures, memes reacting to religion-related news, memes deifying non-religious figures such as celebrities, spoofs of religious images, and video-based memes.[71]

Healthcare

Social media platforms can increase the speed of dissemination of evidence-based health practices.[72] A study by Reynolds and Boyd found the majority of participants (who were healthcare staff) felt that memes could be an appropriate means of improving healthcare worker's knowledge of and compliance with infection prevention practices.[73] Internet memes were also used in Nigeria to raise awareness of the COVID-19 pandemic, with healthcare professionals using the medium to disseminate information on the virus and its vaccine.[74]

Copyright

Since many memes are derived from pre-existing works, it has been contended that memes violate the copyright of the original authors. However, some view memes as falling under the ambit of fair use in the United States.[75][76] This dilemma has caused conflict between meme producers and copyright owners: for example, Getty Images' demand for payment from the blog Get Digital for publishing the "Socially Awkward Penguin" meme without permission.[77]

United States

Under United States copyright law, copyright protection subsists in "original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression, now known or later developed, from which they can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated, either directly or with the aid of a machine or device". It is disputed whether the use of memes constitutes copyright infringement.[75]

Fair use is a defence under U.S. copyright law which protects work made using other copyrighted works.[78] Section 107 of the 1976 Copyright Act outlines four factors for analysis of fair use:

- The purpose and character of the use,

- The nature of the copyrighted work,

- The amount and substantiality of the portion used, and

- The effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.[75]

The first factor implies the secondary use of a copyrighted work should be "transformative" (that is, giving novel meaning or expression to the original work); many memes fulfil this criterion, placing pieces of media in a new context to serve a different purpose to that of the original author. The second factor favours copied works drawing from factual sources, which may be problematic for memes derived from fictional works (such as films). Many of these memes, however, only use small portions of such works (such as still images), favouring an argument of fair use per the third factor. With regards to the fourth factor, most memes are non-commercial in nature and thus would not have adverse effects on the potential market for the copyright work.[75] Given these factors, and the overall reliance of memes on appropriation of other sources, it has been argued that they deserve protection from copyright infringement suits.[78]

Non-fungible tokens

Some individuals who are subjects of memes (and thus the copyright holders) have made money through sale of non-fungible tokens (NFTs) in auctions.[79] Ben Lashes, a manager of numerous memes, stated their sales as NFTs made over US$2 million and established memes as serious forms of art.[80] One example is Disaster Girl, based on a photo of Zoe Roth at age 4 taken in Mebane, North Carolina, in January 2005.[80] After this photo became famous and was used hundreds of times without permission, Roth decided to sell the original copy as an NFT for US$539,973 (equivalent to $607,146 in 2023[81]), with agreement for a further 10 percent share of any future sales.[82]

See also

References

- ^ Benveniste, Alexis (January 26, 2022). "The Meaning and History of Memes". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 28, 2023. Retrieved January 28, 2023.

- ^ Shifman, Limor (April 2013). "Memes in a Digital World: Reconciling with a Conceptual Troublemaker". Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 18 (3): 364. doi:10.1111/jcc4.12013. hdl:11059/14843. S2CID 28196215.

- ^ a b c Brown, Helen (September 29, 2022). "The surprising power of internet memes". BBC. Archived from the original on January 28, 2023. Retrieved January 28, 2023.

- ^ a b c Shifman, Limor (2013). Memes in Digital Culture. MIT Press. pp. 2–4, 20–22. ISBN 978-0-262-31770-2.

- ^ a b Miltner, Kate M. (August 1, 2014). "'There's no place for lulz on LOLCats': The role of genre, gender, and group identity in the interpretation and enjoyment of an Internet meme". First Monday. doi:10.5210/fm.v19i8.5391.

- ^ Knobel, Michele; Lankshear, Colin (2018) [2007]. "Online memes, affinities, and cultural production.". A New Literacies Sampler. Peter Lang Publishing. pp. 201–202. ISBN 9780820495231. Archived from the original on April 5, 2023. Retrieved March 19, 2023.

- ^ Castaño Díaz, Carlos Mauricio (September 25, 2013). "Defining and characterizing the concept of Internet Meme". CES Psicología. 6 (2): 97–98. ProQuest 1713930915.

- ^ Bauckhage, Christian (August 3, 2021). "Insights into Internet Memes". Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media. 5 (1): 42–49. doi:10.1609/icwsm.v5i1.14097. S2CID 16629837.

- ^ Wang, Lin; Wood, Brendan C. (November 2011). "An epidemiological approach to model the viral propagation of memes". Applied Mathematical Modelling. 35 (11): 5447. doi:10.1016/j.apm.2011.04.035.

- ^ Zetter, K. (February 29, 2008). "Humans Are Just Machines for Propagating Memes". Wired. Archived from the original on February 2, 2014. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- ^ a b Coscia, Michele (April 5, 2013). "Competition and Success in the Meme Pool: a Case Study on Quickmeme.com". arXiv:1304.1712 [physics.soc-ph]. Paper explained for laymen by Mims, Christopher (June 28, 2013). "Why you'll share this story: The new science of memes". Quartz. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013.

- ^ Basulto, Dominic (July 5, 2013). "Have Internet memes lost their meaning?". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on July 5, 2013.

- ^ Dawkins, Richard (1989). The Selfish Gene (2 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-19-286092-7. Archived from the original on March 16, 2015. Retrieved June 16, 2015.

- ^ a b Kulkarni, Anushka (June 3, 2017). "Internet Meme and Political Discourse: A Study on the Impact of Internet Meme as a Tool in Communicating Political Satire" (PDF). Journal of Content, Community & Communication Amity School of Communication. 6: 13. SSRN 3501366.

- ^ Godwin, Mike (October 1, 1994). "Meme, Counter-meme". Wired. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ Solon, Olivia (June 20, 2013). "Richard Dawkins on The Internet's hijacking of the word 'meme'". Wired UK. Archived from the original on July 9, 2013.

- ^ Shifman, Limor (April 2013). "Memes in a Digital World: Reconciling with a Conceptual Troublemaker". Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 18 (3): 367. doi:10.1111/jcc4.12013. hdl:11059/14843.

- ^ Keep, Lennlee (October 8, 2020). "From Kilroy to Pepe: A Brief History of Memes". Public Broadcasting Service. Archived from the original on March 6, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Watercutter, Angela; Grey Ellisby, Emma (April 1, 2018). "The WIRED Guide to Memes". Wired. Archived from the original on February 1, 2019. Retrieved November 30, 2018.

- ^ "We who spoke LOLcat now speak Doge". Gizmodo. December 11, 2013. Retrieved January 3, 2024.

- ^ Boutin, Paul (May 9, 2012). "Put Your Rage Into a Cartoon and Exit Laughing". The New York Times. Archived from the original on March 14, 2021. Retrieved November 7, 2020.

- ^ Denisova, Anastasia (2020). Internet Memes and Society: Social, Cultural, and Political Contexts. New York, NY: Routledge. pp. 9–11. ISBN 978-0-429-46940-4. OCLC 1090540034.

- ^ Beran, Dale (2019). It Came from Something Awful: How a Toxic Troll Army Accidentally Memed Donald Trump into Office. St. Martin's Publishing Group. p. xi. ISBN 978-1-250-18974-5.

- ^ Michaels, Sean (March 19, 2008). "Taking the Rick". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 31, 2023. Retrieved January 31, 2023.

- ^ Nieubuurt, Joshua Troy (January 15, 2021). "Internet Memes: Leaflet Propaganda of the Digital Age". Frontiers in Communication. 5: 3. doi:10.3389/fcomm.2020.547065.

- ^ a b Hanlon, Annmarie; Tuten, Tracy L., eds. (2022). The SAGE Handbook of Social Media Marketing. SAGE. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-5297-4378-4.

- ^ "Dank meme". Dictionary.com. Archived from the original on November 30, 2018. Retrieved November 30, 2018.

- ^ Hoffman, Ashley (February 2, 2018). "Donald Trump Jr. Just Became a Dank Meme, Literally". Time. Archived from the original on May 1, 2018. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ^ Griffin, Annaliese (March 9, 2018). "What does "dank" mean? A definition of everyone's new favourite adjective". Quartz. Archived from the original on May 19, 2018. Retrieved May 19, 2018.

- ^ Plaugic, Lizzie (January 10, 2017). "How a group of Redditors is creating a fake stock market to figure out the value of memes". The Verge. Archived from the original on December 11, 2018. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- ^ Günseli, Yalcinkaya (November 11, 2022). "Deep-fried memes: what are they and why do they matter?". Dazed. Archived from the original on February 12, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ Matsakis, Louise (August 30, 2017). "How to Deep-Fry a Meme". Vice. Archived from the original on February 12, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ Hathaway, Jay (November 5, 2018). "The 'E' meme shows just how weird memes can get". The Daily Dot. Archived from the original on March 26, 2019. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ Bruenig, Elizabeth (August 11, 2017). "Why is millennial humor so weird?". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on May 7, 2019. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ Andaloro, Angela (July 22, 2024). "Origins of the Thousand Yard Stare meme". The Daily Dot. Retrieved January 25, 2025.

- ^ Lee, Bruce Y. (December 2, 2018). "They Did Surgery On A Grape: What Is This New Viral Meme?". Forbes. Archived from the original on February 1, 2023. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Ktena, Natalie (September 28, 2018). "Why does everybody love moth memes?". BBC Three. Archived from the original on October 21, 2018. Retrieved February 1, 2023.

- ^ Bryan, Chloe (February 6, 2019). "Surreal memes deserve their own internet dimension". Mashable. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved March 26, 2019.

- ^ Bain, Ellissa (September 10, 2021). "9/10/21 meme explained: What is happening today?". HITC. Archived from the original on February 2, 2023. Retrieved February 2, 2023.

- ^ Herrman, John (February 22, 2020). "Vine Changed the Internet Forever. How Much Does the Internet Miss It?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 26, 2022. Retrieved February 2, 2023.

- ^ Carman, Ashley (April 29, 2020). "TikTok reaches 2 billion downloads". The Verge. Archived from the original on July 29, 2020. Retrieved February 2, 2023.

- ^ Jennings, Rebecca (February 4, 2020). "The most popular dances now come from TikTok. What happens to their creators?". Vox. Archived from the original on February 2, 2023. Retrieved February 2, 2023.

- ^ "Parents and Gen Alpha kids are having unintelligible convos because of 'brainrot' language". NBC News. August 10, 2024. Retrieved September 16, 2024.

- ^ Roy, Jessica (June 13, 2024). "If You Know What 'Brainrot' Means, You Might Already Have It". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved August 26, 2024.

- ^ Flor, Nick (December 11, 2000). "Memetic Marketing". InformIT. Archived from the original on January 14, 2012. Retrieved July 29, 2011.

- ^ McCrae, James (May 8, 2017). "Meme Marketing: How Brands Are Speaking A New Consumer Language". Forbes. Archived from the original on March 15, 2018. Retrieved December 10, 2018.

- ^ Carr, David (May 29, 2006). "Hollywood bypassing critics and print as digital gets hotter - Business - International Herald Tribune". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 3, 2012. Retrieved February 4, 2023.

- ^ Pegolo, Valentina; Carpenter, Lucie (February 6, 2021). "Why Memes Will Never Be Monetized". Jacobin. Archived from the original on February 25, 2021. Retrieved February 7, 2021.

- ^ Whitten, Sarah (January 4, 2017). "A Wendy's tweet just went viral for all the wrong reasons". CNBC. Archived from the original on November 4, 2021. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ^ Rossolillo, Nicholas (September 23, 2021). "What Are Meme Stocks?". The Motley Fool. Archived from the original on November 13, 2021. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ Phillip, Matt; Marcos, Coral M. (August 4, 2021). "Robinhood's shares jump as much as 65 percent, like the meme stocks it enabled". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 18, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

- ^ Popper, Nathaniel; Browning, Kellen (January 29, 2021). "The 'Roaring Kitty' Rally: How a Reddit User and His Friends Roiled the Markets". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 29, 2021. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

- ^ Chohan, Usman W.; Van Kerckhoven, Sven (2023). Activist Retail Investors and the Future of Financial Markets. pp. 99–101. doi:10.4324/9781003351085. ISBN 978-1-00-335108-5. S2CID 257228199.

- ^ Nani, Albi (December 2022). "The doge worth 88 billion dollars: A case study of Dogecoin". Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies. 28 (6): 1719–1721. doi:10.1177/13548565211070417. S2CID 247685455.

- ^ Yozzo, John (April 2023). "Meme Stock Values Can Persist in Bankruptcy, but Cannot Prevail Without Business Justification". American Bankruptcy Institute Journal. 42 (4): 36–37, 70–71. ProQuest 2794896398.

- ^ Seiffert-Brockmann, Jens; Diehl, Trevor; Dobusch, Leonhard (August 2018). "Memes as games: The evolution of a digital discourse online". New Media & Society. 20 (8): 2862–2863. doi:10.1177/1461444817735334. S2CID 206729243.

- ^ Grygiel, Jennifer (May 17, 2019). "Political cartoonists are out of touch – it's time to make way for memes". The Conversation. Archived from the original on October 6, 2021. Retrieved March 6, 2021.

- ^ Murray, Mark (January 18, 2019). "As the 'Dean scream' turns 15, its impact on American politics lives on". NBC News. Archived from the original on May 19, 2022. Retrieved February 7, 2023.

- ^ MacLeod, Alan (February 2019). "Book review: Kill all normies: Online culture wars from 4chan and Tumblr to Trump and the alt-right". New Media & Society. 21 (2): 535–537. doi:10.1177/1461444818804143. S2CID 67774146.

- ^ Stuart, Tessa (February 26, 2016). "Is Ted Cruz the Zodiac Killer? Maybe, Say Florida Voters". Rolling Stone. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ^ a b McLoughlin, Liam; Southern, Rosalynd (February 2021). "By any memes necessary? Small political acts, incidental exposure and memes during the 2017 UK general election". The British Journal of Politics and International Relations. 23 (1): 78–79. doi:10.1177/1369148120930594. S2CID 225602095.

- ^ Lorenz, Taylor (February 13, 2020). "Michael Bloomberg's Campaign Suddenly Drops Memes Everywhere". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 13, 2020. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ Tiffany, Kaitlyn (February 28, 2020). "You Can't Buy Memes". The Atlantic. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved July 30, 2020.

- ^ Placido, Dani Di (May 9, 2017). "How 'Pepe The Frog' Became A Symbol Of Hatred". Forbes. Archived from the original on February 8, 2023. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Victor, Daniel (August 19, 2019). "Hong Kong Protesters Love Pepe the Frog. No, They're Not Alt-Right". The New York Times. Archived from the original on August 19, 2019. Retrieved February 8, 2023.

- ^ Harbo, Tenna Foustad (December 2022). "Internet memes as knowledge practice in social movements: Rethinking Economics' delegitimization of economists". Discourse, Context & Media. 50: 8. doi:10.1016/j.dcm.2022.100650. S2CID 252906293.

- ^ Gal, Noam; Shifman, Limor; Kampf, Zohar (September 2016). "'It Gets Better': Internet memes and the construction of collective identity". New Media & Society. 18 (8): 1698. doi:10.1177/1461444814568784. S2CID 206728484.

- ^ Sample, Ian; Woolf, Nicky (July 27, 2016). "How the ice bucket challenge led to an ALS research breakthrough". The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 8, 2017. Retrieved February 11, 2023.

- ^ Milner, Ryan M. (October 2013). "Pop polyvocality: internet memes, public participation, and the occupy wall street movement". International Journal of Communication. 7: 2357. Gale A352494259.

- ^ Haden Church, Scott; Feller, Gavin (January 2, 2020). "Synecdoche, Aesthetics, and the Sublime Online: Or, What's a Religious Internet Meme?". Journal of Media and Religion. 19 (1): 12. doi:10.1080/15348423.2020.1728188. S2CID 213540194.

- ^ a b Aguilar, Gabrielle K.; Campbell, Heidi A.; Stanley, Mariah; Taylor, Ellen (October 3, 2017). "Communicating mixed messages about religion through internet memes". Information, Communication & Society. 20 (10): 1502–1509. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2016.1229004. S2CID 151721706.

- ^ Cawcutt, Kelly A.; Marcelin, Jasmine R; Silver, Julie K (August 27, 2019). "Using social media to disseminate research in infection prevention, hospital epidemiology, and antimicrobial stewardship". Infection Control & Hospital Epidemiology. 40 (11): 969–971. doi:10.1017/ice.2019.231. PMID 31452490. S2CID 201757947. Archived from the original on February 12, 2023. Retrieved February 12, 2023.

- ^ Reynolds, Staci; Boyd, Shelby (July 2021). "Healthcare worker's perspectives on use of memes as an implementation strategy in infection prevention: An exploratory descriptive analysis". American Journal of Infection Control. 49 (7): 969–971. doi:10.1016/j.ajic.2020.11.019. PMID 33249101. S2CID 227234896.

- ^ Msughter, Aondover Eric; Iman, Maryam Lawal (March 15, 2020). "Internet Meme as a Campaign Tool to the Fight against Covid-19 in Nigeria" (PDF). Global Journal of Human-Social Science. 20 (A6): 27.

- ^ a b c d Scialabba, Elena E. "A Copy of a Copy of a Copy: Internet Mimesis and the Copyrightability of Memes". Duke Law & Technology Review. 18 (1): 340–341, 344–346. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ Schwartz, Benjamin D. (August 5, 2022). "Who Owns Memes?". The National Law Review. Retrieved August 20, 2023.

- ^ Iyer, Aishwaria S.; Mehrotra, Raghav (February 26, 2017). "A critical analysis of memes and fair use". Rostrum's Law Review. 4 (1): 2–3.

- ^ a b Mielczarek, Natalia; Hopkins, W. Wat (March 2021). "Copyright, Transformativeness, and Protection for Internet Memes". Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly. 98 (1): 53–55. doi:10.1177/1077699020950492. S2CID 225023573.

- ^ Pritchard, Will (April 16, 2021). "They were ancient internet memes. Now NFTs are making them rich". Wired UK. Archived from the original on November 14, 2021. Retrieved May 4, 2021.

- ^ a b Fazio, Marie (April 29, 2021). "The World Knows Her as 'Disaster Girl.' She Just Made $500,000 Off the Meme". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 29, 2021. Retrieved April 30, 2021.

- ^ 1634–1699: McCusker, J. J. (1997). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States: Addenda et Corrigenda (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1700–1799: McCusker, J. J. (1992). How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (PDF). American Antiquarian Society. 1800–present: Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Retrieved February 29, 2024.

- ^ Howard, Jacqueline (April 30, 2021). "'Disaster girl', now aged 21, sells original meme photo as an NFT for an eye-watering $650,000". ABC News. Archived from the original on February 14, 2023. Retrieved February 14, 2023.

Further reading

Books

- Blackmore, Susan (2000). The Meme Machine. OUP Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-157461-0.

- Distin, Kate (2005). The Selfish Meme: A Critical Reassessment. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-60627-1.

- Mina, An Xiao (2019). Memes to Movements: How the World's Most Viral Media Is Changing Social Protest and Power. Beacon Press. ISBN 978-0807056585.

- Shifman, Limor (2013). Memes in Digital Culture. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-31770-2.

Articles

- Wiggins, Bradley (September 22, 2014). "How the Russia-Ukraine crisis became a magnet for memes". The Conversation.

- Wiggins, Bradley E; Bowers, G Bret (December 2015). "Memes as genre: A structurational analysis of the memescape". New Media & Society. 17 (11): 1886–1906. doi:10.1177/1461444814535194. S2CID 30729349.

External links

Media related to Internet memes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Internet memes at Wikimedia Commons